By Esperanza Pallana, Community Vision’s Senior Program Officer

We believe gatherings like our 2019 FreshWorks Summit are important opportunities to hear directly from entrepreneurs in disinvested communities. It is their experiences that embody the health, economic, and social inequities of our food and financing systems. For healthy food access to be a reality for all communities we (i.e. financial institutions) have to listen and learn how we can best provide support. To put this value into practice, this year’s Summit was designed a bit differently from previous years.

In past years, the Summit has been a place for lenders and funders who focus on healthy food access to come together to discuss trends in the field of healthy food financing. This year, we engaged our full range of stakeholders because we wanted the conversations grounded in the reality of the type of entrepreneurs and organizations that FreshWorks aims to support. We invited nonprofit leaders and entrepreneurs seeking to address issues of food security and healthy food access in their communities, technical assistance providers helping to build capacity for organizations and businesses, lenders who are innovating ways to financially back community-based projects and businesses, and people with an interest in healthy and equitable food systems to attend and help design the Summit.

Our commitment to listening is rooted in our knowing that people have the solutions to the issues they face. As such, the 2019 Summit was informed by previous years of organizing work in the San Joaquin Central Valley and FreshWorks’ stakeholders. The planning started with a stakeholder survey to identify the topics of greatest interest. From the results we learned that there was a strong desire for a nuanced discussion of how people are operationalizing racial equity to address structural racism in the food and financing systems. Specifically, people were interested in how to scale hyper-local solutions, remove barriers to capital for businesses, and to learn about the different types of models of healthy food access that exist in California’s rural and urban neighborhoods. This feedback became the topics featured in the breakout sessions.

Along with opening up the planning process, we also wanted to center power building, equity, and racial justice. To honestly do this we knew we had to hear directly from the people who are most impacted by the social and economic inequities that FreshWorks was created to address. Panels included individuals who are developing food projects or operating food-related businesses along with the institutional partners who have traditionally convened at the FreshWorks Summit. As panelists, the folks working on their business or project to increase healthy food access had a platform to describe, in their own words and stories. what they need, the barriers they face, and how some have successfully navigated those barriers. Throughout the day, investors, funders, lenders, and other attendees had the opportunity to hear from individuals about their firsthand experience with financial disinvestment and discrimination.

In the morning session, Rural Communities: Context & Strategies, Dennis Hutson, a retired Air Force Chaplain and retired United Methodist Pastor, shared his story about why he founded The Allensworth Corporation (TAC). Located on 60 acres of farm land that was purchased from an aging farmer, TAC’s mission is to help revitalize the town of Allensworth through a community owned and operated closed loop organic farming system that produces rabbits, fertilizer, earthworms, and specialty crops. Allensworth is a small town located about 40 miles north of Bakersfield. It was established in 1908 as the first all-black town in California by a group of African American men led by Colonel Allen Allensworth.

Located in the Central Valley, Allensworth started building a strong agriculturally-based economy. After not receiving water that was rightfully theirs the town’s economy declined as farmers left to work elsewhere. Allensworth’s economy and population saw further decline in the 1940s as people left for war industry jobs in the Bay Area, and again in the late 1960s when arsenic was found in the water. Hutson now preaches through his actions as he works with others to cultivate a locally-based food system as an economic driver for the people tending the land and greater Allensworth community.

“My responsibility is to be faithful to what I was given to do. My actions will hopefully inspire people and give people hope. If people have hope, then they can start to look at possibilities for a better life.”

– Dennis Hutson, The Allensworth Company

During the lunch session, In Real Time with Food Projects, Neelam Sharma of Community Services Unlimited, Brahm Ahmadi of Community Foods Market and Warren King of Food Commons Fresno, discussed successes and barriers to their large scale community-driven economic development projects. Sharma shared about the Paul Robeson Community Wellness Center, a project of Community Services Unlimited, in South Los Angeles. A significant takeaway from this session is that while resources like FreshWorks are successful in leveraging innovative approaches to address complicated issues, projects at this scale still take a long time to come to fruition and for impact to manifest.

In the afternoon session, Beyond Grocery Retail: Alternative Approaches to Increasing Healthy Food Access, Samantha Chacon-Lopez shared about her family’s path to creating Urban Foodies; a start-up that provides nutritious and affordable pre-packaged meals. Urban Foodies grew out of the family’s personal need for affordable healthy meals. After both her and her husband lost their jobs and through her son’s personal health journey, Chacon-Lopez realized how difficult it was to access affordable, healthy, and tasty food options in her family’s neighborhood.

A striking difference was the extremely low access to healthy, pre-made food options in South West Fresno when compared to neighborhoods in North Fresno. Born and raised in Fresno, Chacon-Lopez is very familiar with the inequitable development across the city’s neighborhoods. In describing her neighborhood’s food environment, she painted a picture that has come to be a typical description of a ‘food desert,’ where processed foods and fast food establishments are plentiful while fresh, whole foods are lacking. What started as a way to nourish her family grew to providing meals for friends and has blossomed into an emerging business that provides homemade meals to people living in the South West Fresno region. Improving healthy food access from within her community, Chacon-Lopez says that Urban Foodies is changing her community “one plate at a time.”

For the current iteration of FreshWorks we designed and implemented the program from the premise that food access is not simply a health issue but it is a community development and equity issue. For us this means that a key part of our work is to support a shift of leadership within the food system.

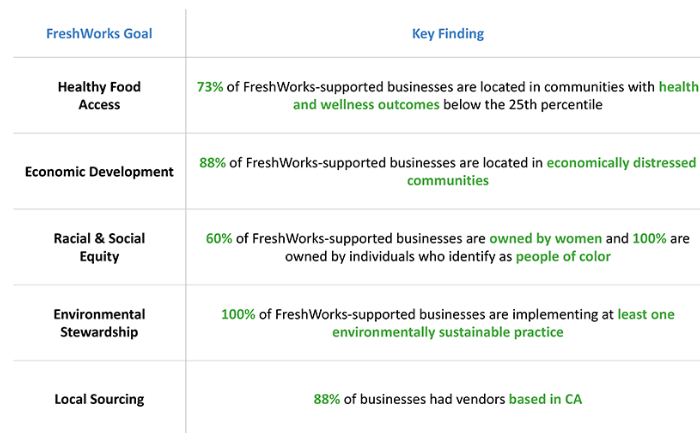

When we look at who is most affected by inequities in the food system, we see it is people of color, women, and low-income individuals. Further, when we look at who has ownership across the food system we see that corporate consolidation is widening inequities in all areas. From seeds to land ownership to retail distribution, profit is the driver of our conventional food system rather than nourishing our communities. In this context, an especially notable highlight of the Summit was sharing our first year of review as the program administrators.

Overall the first year’s key findings, highlighted in the chart above, underscore the potential for catalytic impact of supporting businesses located within financially oppressed communities that are owned and operated by people who are often labeled as “high-risk.”

Pacific Community Ventures (PCV) served as our program evaluators. Through interviews of FreshWorks supported businesses, PCV learned that the businesses tend to hire directly from the community that they are based in; employees are recruited via personal relationships of the owners and other employees. These findings are significant because it can help change the narrative of whose businesses are or are not worthy of investment. The findings also connect back to why FreshWorks exists – the overlap between communities that lack access to healthy foods and the communities that have experienced decades of disinvestment.

The healthy food financing field must prioritize resourcing businesses and projects led by people of color and low-income people; the people who come from financially oppressed communities. Part of this process includes creating intentional platforms where entrepreneurs from these communities can speak about their experiences in order to educate lenders, investors, and funders on what is working and where improvements can be made.

FreshWorks supports community-led enterprises with big visions because we know that they are realistic and achievable when resourced in a way that meets their needs. What we learned at this year’s Summit will help to inform future FreshWorks services and products as well as next year’s Summit.

Esperanza Pallana is Community Vision’s Senior Program Officer. She has been with the organization since 2016 and supports the management of the California FreshWorks program.