June 1st, 2019 marks the official opening of Community Foods Market (CFM) at 3105 San Pablo Avenue in West Oakland. This article celebrates CFM’s grand opening as a moment years in the making and only possible because of the work and dedication of many people. It also celebrates CFM as a model of what it looks like to align capital with economic and racial equity, where health, community-driven ideas, and economic empowerment are at the heart of their business model.

Brahm Ahmadi, Community Foods Market CEO, has spearheaded the effort to bring this community-oriented grocery store to West Oakland. Voted East Bay Express’ Best Follow Through in 2018, Ahmadi began this path in 2002 when he co-founded People’s Grocery and renovated an old postal truck into a mobile food market with scheduled stops around West Oakland. Recognizing the need for a brick and mortar that could serve more people but constrained by a lack of capital and the barriers of entrance to capital, Ahmadi spent years organizing and raising funds to bring the market to fruition.

It is not by accident that West Oakland lacks fresh, affordable, and nutritious food options. A ‘persistent poverty map’ created by the Alameda County Department of Public Health shows the connection between poverty and zip code and how these dynamics have been shaped by a history of racist and discriminatory lending policies and practices, residential development, suburbanization, and city planning. Notably, the map underscores that structural processes have fostered deep inequities between Oakland’s flatlands and hills neighborhoods.

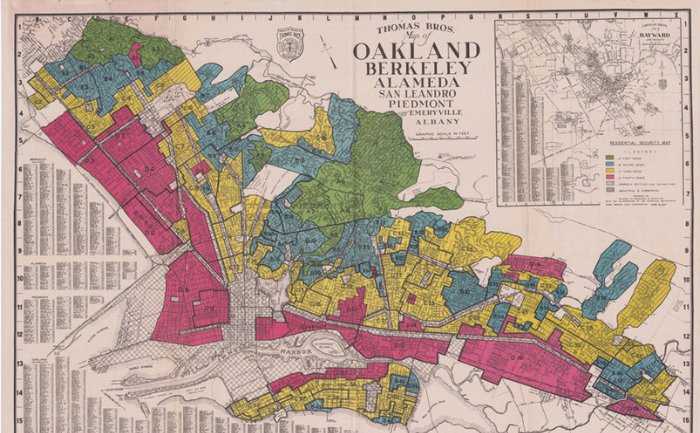

A now well-known set of maps are the ‘residential security maps’ created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). The image above is a 1937 residential security map of Oakland and surrounding cities. HOLC was established in 1933 as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs under the Homeowners Refinancing Act. As a government agency one of HOLC’s responsibilities was to develop a system to help banks identify investment risk at the neighborhood level in various cities across the United States. They developed a letter-graded system that includes: “A- best,” “B- still desirable,” “C- definitely declining,” and “D- Hazardous,” where each color-coded map is a visual representation of different neighborhood’s grades. This letter and color-coded system is not based on an individual’s qualifications or credit standing, but rather, it is based on judgements about people with low-income, people of color, and foreign-born individuals. Predominately white and wealthier neighborhoods were deemed desirable and therefore receive higher grades based on HOLC’s system. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), created as part of the National Housing Act of 1934 and also part of the New Deal, used HOLC’s maps to determine approval of loans and mortgages. This discriminatory practice, known as redlining, meant that people living in the neighborhoods within the red lines were denied financial services or received low-quality services based on their race, ethnicity, and/or economic status.

In Northern California, of the 350,000 federally backed loans between the years 1946 – 1960 fewer than 100 went to African American families; more than 98% of these loans were given to white families. This legacy of financial neglect shows up in the wealth and health of a community. While FHA focused only on home loans, the impact of their discriminatory practices extended into investment in commercial and public spaces for whole neighborhoods. Oakland’s flatlands are a clear example of how financial discrimination contributed to the disparities in the availability and quality of community assets like grocery stores, thriving small businesses, maintained streets, and parks and green space.

As a community development financial institution, Community Vision is dedicated to aligning capital with justice and equity to address the history of discriminatory financial practices and intentional disinvestment. Community Vision works to remove barriers that have contributed to a lack of economic progress in low-income communities and communities of color. As the administrators of FreshWorks, capital is the tool and food is the medium to invest in the health and wealth of California’s communities.

Disinvestment of whole communities doesn’t happen overnight and neither do the solutions, Community Vision’s collaboration with CFM can attest that truth. Community Vision has had the privilege to be a partner alongside Brahm Ahmadi since 2016. Before that, Cat Howard, Community Vision’s director of Strategic Initiatives, was involved in awarding what was then People’s Community Market with FreshWorks’ first grant in 2012. Since then, Community Vision has developed a partnership with Brahm that goes beyond providing financial support to include deep respect and a reciprocal relationship, supporting each other on panel discussions, at community events and media engagements, and with funding connections and investor engagements.

Realizing that traditional funding streams were not going to back a non-traditional grocery store going into a disinvested community, Brahm turned to the community to raise funds through a direct public offering to California residents. The DPO campaign raised more than $2.2MM in investments from nearly 650 California resident shareholders, which made it possible to secure ongoing financing from other sources. Unlike traditional venture capital or start up investments, the funds raised from the DPO will be patient equity that does not extract outsized returns from the CFM and its local community.

Over the last eight years, FreshWorks and Community Vision have invested in CFM in a number of ways. The early FreshWorks grant provided seed capital for the company’s capital raise. A FreshWorks’ credit enhancement unlocked more than $17MM financing from its network of lenders. In the Summer of 2016, Community Vision provided CFM with a $25,000 dollar grant from the Greater Oakland Fund (Go Fund) that covered the often difficult to finance site-specific pre-development costs. Later, in 2017 Community Vision and FreshWorks provided a $3,477,000 construction loan, and FreshWorks supported an additional construction loan from Self Help Federal Credit Union. In 2018, Community Vision, Clearinghouse CDFI, and the Nonprofit Finance Fund provided a $6.1MM NMTC leverage loan with FreshWorks credit enhancement. As well, Community Vision provided $11 MM in NMTC. Finally, both Community Vision and FreshWorks further supported the CFM’s Direct Public Offering with matching investments at critical junctures as the project needed to attract equity investments.

When Community Foods Market acquired land at San Pablo Ave. and Myrtle St. there were critics who suggested that the store would never sustain itself in the neighborhood. But the people who said that the store is needed and will thrive were the people living in the community. At Community Vision we strongly believe that communities know what they can achieve, which is why we have always believed in the vision of CFM Principal Brahm Ahmadi. Community Vision understands the potential for good that a locally owned market, focused on stocking fresh, healthy foods, and creating new jobs in a community-focused setting could have for the area.

“As a social justice catalyst, Community Vision uses capital to support communities in accessing space and unlocking financing that would otherwise be inaccessible.”

– Catherine Howard, Community Vision’s Director of Strategic Initiatives and Director of California FreshWorks

Going back to that 1937 residential security map of Oakland, you can see that Community Foods Market is located in what was designated a D8-graded area. From a historical point of view, it can seem logical for traditional financers to see risk over great possibilities because they have been conditioned by decades of ‘business as usual’. But as we clear up our understanding of that historical context, then we can see that the logic is flawed and leads to investment decisions based on racist ideologies.

Investing in projects like Community Foods Market is part of what it takes to change the paradigm of what risk is. For Community Vision, risk is when a community lacks access to healthy foods. Risk is when people do not have meaningful employment. Risk is denying financial services to projects that prioritize community voice and community ownership.

CFM’s strategic vision is to serve as a catalyst for building wealth and health, while also providing a social gathering space in a neighborhood that has experienced decades of disinvestment. This is not the business model of a typical chain grocery store. This is the model of a company that has a deep understanding of the community that it serves.

For over two years, Brahm convened a neighborhood advisory committee to gather input and feedback on what the market would offer. Community Foods Market has taken the community voice to heart, which shows in the physical design and offerings of the market. One of the biggest additions to the design was the Front Porch Cafe, which will open an hour before and close an hour after the market. While not in the original plans, the design team added the Front Porch because of the community’s strong desire for a social gathering space where people can connect and enjoy live music. Something that Brahm is most proud of is the fact that nearly 80% of CFM’s employees live within half a mile from the market. Hiring from the community was an important goal, and Brahm believes that it will be key to sustaining the market.

“This store will be a catalyst for economic development in the neighborhood. We want to support local community members in becoming more resilient so that they can fight the forces of gentrification more easily. We want the community to really feel like this is their store.”

– Brahm Ahmadi, Community Foods Market’s CEO.

Community Vision stands proudly with Community Foods Market to show that it is possible for those who have been most marginalized to be involved in shaping the wealth providing opportunities of their community.